There are some artists, and Tom Hanks is one, who go beyond mere popularity and instead come to embody some part of our shared American story. Ever since the actor broke out from a string of roles as a goofy, lovelorn leading man via the complicated innocence of his work in “Big” (1988), Hanks has gradually become an avatar of American goodness. Over the course of his long career, he has found clever ways to convey a fundamental and aspirational decency. He has played honorable men on society’s then-margins (the discriminated-against gay lawyer of “Philadelphia”) and at the center of our history (“Forrest Gump”; “Apollo 13”). At other times, he has found ways to imbue with can-do optimism characters who are caught in the middle of seemingly unbearable situations, whether they’re alone (“Cast Away”) or surrounded by enemies (“Saving Private Ryan”). Such is the malleability of his gift that he has created trustworthy portraits of real-life characters (the heroic airline and cargo-ship captains of, respectively, “Sully” and “Captain Phillips”), cartoons (Woody the cowboy from the “Toy Story” films) and real-life characters who easily could have come off like cartoons (as Fred Rogers in “A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood”).

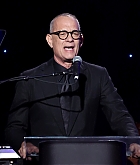

Is it telling, then, that in this time of declining trust in our institutions and one another, Tom Hanks is now playing a bad guy? One with a hand in the downfall of another American icon and myth maker? But in true Hanksian fashion he finds something unexpectedly hopeful even in this character. “I’m not interested in malevolence; I’m interested in motivation,” Hanks says about his role as the shadowy talent manager, Col. Tom Parker, in the director Baz Luhrmann’s biopic “Elvis,” which premieres June 24. “All you can say is that he’s wrong,” he adds, “not evil.” There’s a useful lesson there. With Hanks, there often is.

Tom Parker was a Dutch guy who passed himself off as a Southern colonel.1 Elvis was a poor kid from Tupelo who turned himself into a superhero. Both were careful to present very specific versions of themselves to the public. What might a movie star like you know about what’s underneath that kind of self-presentation that the rest of us don’t? Well, I don’t think in show business there were more authentic-to-themselves personalities than those two. Elvis dressed the way he dressed because he had to. He felt he looked good. Onstage, he wasn’t wiggling to say, “Hey, time to turn on the sex appeal.” It was instinct. Col. Tom Parker was the same exact type of thing on a crass, nonartistic level. I heard a story: When he was a carny, he had a dime welded to his ring. He’d say: “That cost 90 cents and you gave me two dollars. I owe you a dollar 10.” He would then take the customer’s hand, put the change in, close it up, say “Thank you very much” and cheat people out of that dime. He got the same pleasure from that as he did signing a deal for Elvis with the International Hotel in Las Vegas for millions of dollars. That’s got nothing to do with power, nothing to do with influence. It is a dispassionate desire to always get this other thing. That was the secret sauce of living for Col. Tom Parker, the same way that his hair and clothes and the music he loved was the secret sauce for Elvis.

That’s them. I’m asking about you. What do you know about the performance of authenticity? Me? You mean career-wise?

However you want to take it. You know, I was not an overnight sensation. I had been in movies for a long time until I had enough opportunities and experience to realize that I don’t have to say yes to everything just because they’re offering me the gig. Some of that was, What am I going to do instead? Wait for the phone to ring? The phone rang! I said yes! But I was fortunate in that my sense of self and artistic thirst grew at the same time. I had done enough romantic leads in enough movies and had experienced enough compromise to say, “I’m not even going to read those scripts anymore.” So then you hold out for something that represents more of the artist you want to be. When Penny Marshall came to me on “A League of Their Own,” I said: “Penny, this is written for a guy who’s older than I am. The character is in his 40s and washed up.” She said: “That’s why I want you. Because this guy should have been great until he was 40 and wasn’t.” I went Aaaah. Before that a director had never said something to me like, “Come up with a reason why you’re 36, broken down and managing a woman’s baseball team.” Then it was, Katie, bar the door! I was looking for more of that from then on. The other thing that happened in the ’90s was when Richard Lovett2 at C.A.A. said, “What do you want to do?” No one had asked me that question, either. People always said: “What do you want to do with this opportunity?” But what do you want to do? I said I’d like to make a movie about Apollo 13. That was the first time where I was saying, “This is the type of artist who I want to be.” But if you look at anybody’s career, there’s hits and misses. There’s movies that simply don’t work, and if something not working is debilitating to you, you’re toast. [More at Source]